Despite being on the radar for many years, illegal mining remains a dangerous, unregulated concern for South Africa’s mining industry and the wider economy.

Illegal artisanal mining in South Africa is among the most lucrative and most violent in Africa, and the practice is deemed one of the biggest sources of illicit gold on the continent.

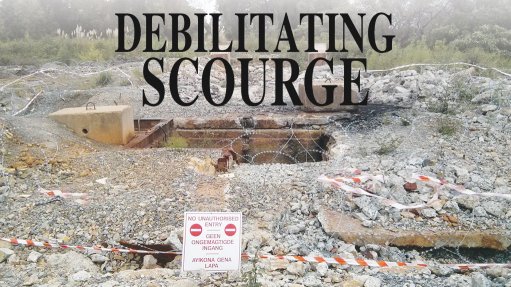

It is estimated that about 30 000 illegal miners, the so-called zama-zamas, work in and around many of the 6 000 disused and ownerless mines across South Africa.

The infiltration of zama-zamas also extends to currently active commercial mines, with the unique phenomenon adding another layer of complexity that is confounding South Africa’s law enforcement agencies, mining officials and the industry, says illicit artisanal mining specialist, independent investigative researcher and technical adviser Alan Martin.

Organised by criminal syndicates, illegal mining is responsible for billions of rands in lost tax revenue, threatens physical infrastructure and public safety and brings major security headaches to established, publicly listed companies.

Unique to South Africa is that illegal miners mostly target underground industrial shafts, as opposed to openpits, as is normally the case, and occurs within large-scale mines, says Martin, who is the author of ‘Uncovered: the Dark World of the Zama Zamas’, the latest policy brief from Enact, a project of the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), Interpol and the Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime.

The study specifically examined the gold sector in South Africa; however, zama-zamas activity cuts across the board and includes diamonds and platinum.

Data from Minerals Council South Africa shows that, over the past year, illegal mining has started to encroach on the diamond fields of Kimberley, in the Northern Cape, and chrome deposits in Limpopo, while there is evidence of illegal mining in the coal industry.

“Illegal mining and precious metals trafficking are complex multilayered international phenomena. Criminal syndicates use elaborate schemes and extensive export routes to successfully sell stolen precious metals to international and local refiners and launder the proceeds with limited detection and subsequent impunity,” explained Brigadier Hennie Flynn of the Directorate for Priority Crime Investigation at an ISS-hosted panel discussion on illegal miners.

A 2015 report estimated that about 10% of South Africa’s gold production – worth about R8-billion – is stolen and smuggled out of the country.

The Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime, meanwhile, believes lost gold production far exceeds R14-billion a year.

Further, in a document submitted to Parliament in March 2017, the Minerals Council estimated lost sales, taxes and royalties at R21-billion a year.

The true cost of illegal mining activity, however, includes damage to public and private infrastructure caused by vandalism or poor mining practices, as well as the costs of security upgrades undertaken by mining companies to address illegal breaches.

According to the Enact report, one mining house surveyed has, since 2013, spent almost R366-million on upgrading its security infrastructure and protocols to make it more difficult for zama-zamas to penetrate the mining precinct and its shafts.

The dangers posed by illegal mining include the uncontrolled use of explosives, which compromises support pillars in decommissioned mines.

This has resulted in tremors and places the structural integrity of roads and adjacent residential communities and businesses at risk.

It also poses a significant public safety threat, as some of the blasting has taken place close to pipelines carrying gas and fuel.

Other risks include the temporary closure of commercial mines, the entrapment of illegal miners underground and the death of, or injuries to, illegal miners.

In addition to being subjected to unsafe, exploitative and precarious working conditions, zama-zamas also face a plethora of dangers, such as extortion, murder, forced migration, money laundering, corruption, racketeering, drugs and prostitution within a market managed by a five-tier system.

Illegal miners constitute the first tier and are responsible for physically mining the coveted minerals underground, while the second tier comprises the buyers, who also organise the first-tier illegal miners and support them with food, protection and equipment.

The third tier comprises the regional bulk buyers, many of whom have permits issued in terms of the Precious Metals Act to trade in precious metal, while the fourth tier contains national or international distributors using front companies or legitimate exporters.

Within the fifth tier are the top international receivers and distributors that work through international refineries and intermediary companies.

The five-tier system shows that the underground workers take the most risks for the least amount of reward.

Hundreds of illegal miners die in mining accidents that are not reported or from which bodies are never recovered, or during below-ground shootouts with mine security or competing syndicates.

While no official record of zama-zama deaths exists, some estimations place fatalities at well over 300 between 2012 and 2015.

About 67% are the result of turf wars, mostly in Gauteng, with the violence in affected areas equated to that of chaotic and conflict-ridden illegal artisanal mine sites in active war zones.

Martin further explains that zama-zamas are emblematic of a changing South African mining landscape – and are a direct by-product of persistent, unanswered socioeconomic inequalities.

Since 1995, employment within the gold mining sector plunged from about 380 000 to about 119 000 in 2014, with Minerals Council South Africa figures showing further declines to 101 085 in 2018.

This has had social ramifications beyond South Africa’s borders, as remittances from mining jobs have sustained local economies in countries such as Lesotho and Mozambique, where unemployment often hovers above 30%.

This social crisis means that unemployed men with mining experience are willing to take their chances as zama-zamas to earn a living.

Further, socioeconomic and political crises in neighbouring countries drive millions of Southern Africans, particularly Zimbabweans, to seek out their fortunes in South Africa.

A research report, ‘Pulling at Golden Webs’, by Marcena Hunter estimates that 70% of zama-zamas are undocumented foreigners.

Solving a Social Dilemma

With many competing approaches to the growing zama-zama infiltration, a paradigm shift is required for South Africa to successfully tackle the challenge.

A more holistic, nuanced and multifaceted approach is required from government and industry to address the lack of formalisation and the marginalisation of the illegal mining sector, says Martin.

While government takes the hardline stance of intermittently using police to subdue and criminalise artisanal miners, Martin believes that this fails to address the underlying socioeconomic factors or the role played by criminal networks in orchestrating and benefiting from illegal mining.

It also fails to acknowledge the economic potential of the zama-zamas and the contribution they make to local economies and those of their home countries.

The extent of the violence and criminality requires the South African gold industry to urgently apply a stricter and more robust risk assessment to its supply chain and overhaul legislation to find ways of harnessing the miners’ economic potential, besides others.

In its current form, despite giving legal recognition to the artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) sector, the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act enables illegal activity and hinders the ability of police to prevent criminality.

“South Africa’s legislation aims to regulate artisanal mining, but has little effect on illegal mining,” says Martin, noting that the existing legislation offers no option for the ASM to coexist with the large-scale mining sector.

However, two South African diamond operations took an unprecedented step in 2018 by allowing zama-zamas to mine tailings on their properties through a cooperation agreement, creating a possible model for other operations to mimic.

While this model is not deemed a feasible option for active gold mines, which have invested heavily in infrastructure, this could be a game changer for South Africa’s disused gold mines and could be considered for similar above-ground mining operations that have been affected by illegal mining.

Such arrangements allow for artisanal and small-scale mining within an industrial concession, but set parameters on how artisanal miners work and sell their production.

Meanwhile, the current Act mandates the South African Diamond and Precious Metals Regulator to license, monitor and investigate mining permit holders – a role that should either be shared with the police or be returned to the exclusive control of the police.

This would provide law enforcement greater latitude and oversight to spot trends, undertake proactive due diligence on permit applicants and monitor the business activities of criminally exposed entities.

Beyond legislative obstacles, a significant challenge to finding a solution to the chaos and criminality of the zama-zamas and the socioeconomic drivers motivating them is one of approach, Martin highlights.

“Criminalising, demonising and scapegoating illegal, and mostly foreign, miners is an easy deflection away from more difficult discussions of uncomfortable truths about the persistent poverty, poor service delivery in marginalised areas and political instability in neighbouring countries that contribute to men becoming zama-zamas in the first place.”

It also ignores the economic significance and contributions of ASMs.

He cites a Bench Marks Foundation argument that the 30 000 zama-zamas in South Africa have a dependence ratio of 1:8, which means that 250 000 people depend on them.

“Shutting down artisanal mining would create another 280 000 victims of unemployment, which would not only increase poverty rates but could also add to South Africa’s already high violent crime rate,” the report notes.

It is suggested that a small-scale mining board be re-established, which could provide skills training for ASM miners, particularly in relation to safe mining practices.

The Minerals Council believes that there is a need to focus on the supply and demand side of illegal mining and deal with all five levels of the syndicates.

“While local police and mine security deal with the first two tiers, the Minerals Council, assisted by the Standing Committee on Security, the South African Police Service, the National Coordinating Strategic Management Team and the Department of Mineral Resources, is working to identify and deal with the next three levels that constitute the buyer market nationally and internationally. This work is undertaken hand in hand with international agencies, such as the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute, European police, Interpol and international embassies,” the organisation outlines in its fact sheets.

Further, suggestions on the centralisation of the system regulating the purchase and processing of precious metals, which would contribute significantly to including zama-zamas in the legal supply chain, are being made.

“A single designated gold buyer, or a small group, would buy at the daily spot price, offering the miners true market value for their gold, thereby incentivising them to operate within a formalised and legal framework,” Martin notes.

“We need to identify global weakness in legislation and control systems, analyse strategies and responses to counter illegal mining, illicit trafficking in precious metals, organised crime and possible terrorist financing,” adds Flynn.

“The combined effect of theft, fraud, conspiracy, an illicit economy, violence, corruption, money laundering and the transnational illicit trafficking in precious metals requires all role-players in the value chain to adopt a robust approach to mitigate and neutralise the threat globally,” he concludes.