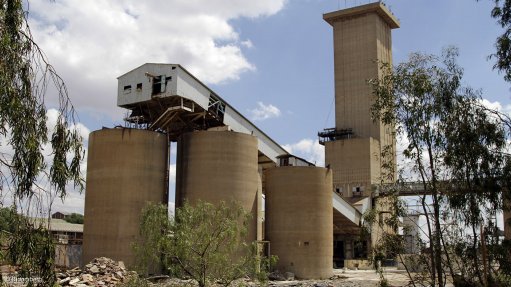

The State is responsible for the environmental- and other closure- related liabilities for ownerless mines

Photo by: Bloomberg

Of the numerous mines in South Africa that have closed down, those which are now ownerless have become the responsibility of the State.

This means that the State is responsible for the environmental- and other closure- related liabilities, says law firm Eversheds Sutherland Mining and Infrastructure head Warren Beech.

These liabilities have prompted the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE) and the Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries to introduce new laws that address mine closure.

“The new laws and regular amendments are aimed at ensuring that mining companies are held responsible for pollution, degradation and rehabilitation . . . by ensuring that appropriate financial provisions are made for the management of rehabilitation during mining operations and after closure,” he explains.

Beech stresses that South Africa’s mining and natural resources sector is facing numerous financial and institutional challenges, which has resulted in mines either being placed on care and maintenance or shutting down completely.

This has, subsequently, led to a focus on the management of mine closure operations, especially for older mines that remain part of a company’s current structure and mining operations.

Additionally, older mines are often targeted for illegal mining, which has impacted on rehabilitation that was previously carried out, exposing the mining company to continued potential liabilities under the mining and environmental laws.

“Illegal mining of old mines creates potential health, safety and environmental risks.

“If, for example, an old coal mine, which was previously rehabilitated, is illegally mined, the new exposure could result in spontaneous combustion,” he says.

Beech adds that as illegal mineworkers and community members often live in close proximity to these defunct operations, this would potentially leave the community exposed to hazards to their health and safety, including burns and toxic fumes, and possibly, damage to property and livestock.

The exposure of the coal from the dumps that are reworked and exposed by illegal miners could also impact on water resources, possibly polluting and degrading raw-water quality, which is problematic in a water-scarce country such as South Africa.

Legal Procedure

The correct procedure for mine closure operations includes the identification of all historical mining operations.

Beech notes that a verification exercise should be carried out to confirm the location, as well as the current and historical ownership, of the mines, the timeframes of all previous mining activity, and the extent of previous rehabilitation.

This will ensure that the appropriate mining and environmental laws can be applied and will identify whether any closure certificates have been issued, or need to be issued.

“It is only through a proper understanding of the mine closure operations and the applicable mining and environment laws that historical mines can be properly managed,” he says.

Beech notes that noncompliance exposes mining companies to potential criminal prosecution. It could also lead to possible suspension or cancellation of any prospecting or mining rights that the company may hold.

Noncompliance is taken into account by the DMRE when considering new applications for prospecting or mining rights or when existing prospecting or mining rights are renewed.

“There is also potential reputational risk . . . where persons are injured, as a result of old mine workings, or when there is damage to property or injury to livestock of members of affected communities . . .”

Nongovernmental organisations and other civil society groups are active in ensuring that noncompliance by mining companies and injuries to community members are brought to the attention of the regulators and the public using social media, Beech adds.

He says other consequences include companies facing potential investor criticism and possible withdrawal of investment.

“Investors are becoming socially aware and are carefully considering investment in mines that present unacceptable risk, particularly from an environmental perspective,” says Beech.

Other Legislative Developments

Recent amendments to the regulations of the Mine Health and Safety Act (MHSA) pertain to trackless mobile machines and electricity, because of historical injuries caused to employees at mines, related to trackless mobile machines and electricity.

The December 2020 deadline to implement stipulations described in the 2015 amendments to the Chapter 8 regulations – which address the safe use of diesel-powered trackless mobile machinery (TMM) – of the MHSA is imminent.

The TMM regulations necessitates that companies, based on an approved risk assessment, implement an automatic detection system, which can audibly and/or visually warn operators of an imminent collision.

Moreover, there must be some automatic intervention by the system to prevent a collision if the operator fails to act, and the TMM must fail to safe, if necessary.

“The regulations regarding TMMs seek to address injury concerns . . . at mines,” states Beech.

He notes that the regulations call for the installation of proximity detection systems that infer when individuals are close to the machinery, issuing appropriate warnings, depending on how far the individual is, or intervening to stop the vehicle or machine.

This is to prevent any injuries or fatalities because of a collision or other interaction with the machinery. The systems also detect other machinery operating in the vicinity and will implement the same fail-safes to avert imminent collisions.

Meanwhile, the MHSA makes provision for investigations and inquiries at mines, where a dangerous situation threatens employee health or an accident occurs, resulting in injury or death.

The Act also covers conveyor belts and their structures, especially those that are supplied or operated by third parties, which need to comply with Section 21 of the MHSA.

“Section 21 states that any person who designs, manufactures, repairs, imports or supplies any article for use at a mine must ensure that the article is safe and without risk to the health and safety of employees when used properly and that the said article complies with all the requirements stated in the MHSA,” he notes.

The Act also places the responsibility for employees and other persons who may be directly affected by activities at the mine on the employer – the entity which holds the prospecting or mining right.

The regulations of the MHSA, with regard to the additional requirements in relation to TMMs, are expected to come into effect in early 2020, Beech concludes.