NEW VIEWS A key driver of innovation is using satellite imagery, which is becoming increasingly available free of charge

Monitoring abandoned mines and illegal mining activities using satellite imagery is now possible, says Hansjörg Eberle, director of Crosstech remediation services provider and subsidiary of the Swiss Foundation for Mine Action.

Crosstech, as part of the Swiss consortium that also includes software company Sarmap, with cofinancing from the European Space Agency (ESA), is aiming to demonstrate how this can be done through an applied research project.

Eberle says such a system will be well suited to South Africa, which has serious difficulties with monitoring abandoned mines and illegal mining activities. He adds that, as the mining sector is in the doldrums, abandoned and mothballed mining sites are likely to increase.

“We are looking for partner organisations (government or commercial) that are willing to participate in a demonstration project, at no cost to them,” he tells Mining Weekly.

He notes that the research project forms part of the ESA’s Advanced Research in Telecommunications Systems (ARTES) 20 Integrated Applications Promotion (IAP) programme.

The ARTES 20 IAP programme is dedicated to the development, implementation and pilot operations of integrated applications. These are applications that combine data from at least two existing and different space assets such as satellite communication, earth observation, satellite navigation and human spaceflight technologies.

“The ultimate aim of the programme is to bring a product or services to market,” Eberle states.

He says several technologies have abundantly been described by researchers, but have not been incorporated into mainstream products or services.

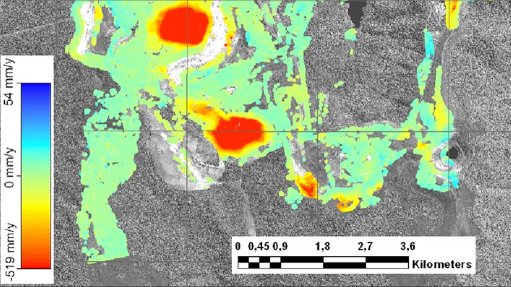

Eberle cites synthetic aperture radar, which can detect changes up to the millimetre by comparing images taken at different times, as an example. This technology can help to detect whether a dam has shifted over the years, whether there is erosion at tailings dams or whether the soil is moving through subsidence. “Such tiny movements are often the precursors for bigger shifts, leading to major disasters, as we have recently seen with the dam break in Brazil.”

Using the same technology also allows for tracing the history of an area for as long as satellite imagery is available (up to 20 years) and drawing conclusions based on the history of what has happened in the past, he adds.

Further, Eberle notes that a key driver of innovation is using satellite imagery, which is becoming increasingly available free of charge, such as the ESA’s series of Sentinel satellites.

He points out that satellite imagery is becoming available more rapidly than in the past and, in some instances, updated satellite imagery can be generated on a monthly or weekly basis. “This allows for monitoring and change detection in almost real time.”

Eberle comments that such techniques will allow for the remote environmental monitoring of mining sites. Most mining companies and regulators continue to monitor sites by driving to and patrolling them or – in some cases – by planting sensors in some locations. While these methods might work for one site, it becomes inefficient and costly when dozens or hundreds of sites have to be monitored.

“We believe we can develop a monitoring system based on actual user requirements using these techniques. The end product could be regularly updated, with detailed risk maps for geologists and high-level risk maps with interpretation and plain language text for decision-makers . . . [which] will be available on the Internet,” he concludes.